Evo Devo intro

Link to "Deep Homology" article.

Embryology

The question of how we go from a single, fertilized egg to a complex organism is one of the most vexing open questions in Biology. Having said that, a lot has been learned in the last 30 years and some general rules and principles can be laid out.

Early events:

When the egg is first formed, it already has polarity to it. That is to say, one side of the egg is not like the other. This is especially obvious in the fruit-fly, which has an oblong egg. Those horns at the end are breathing tubes.

.

Figure 1

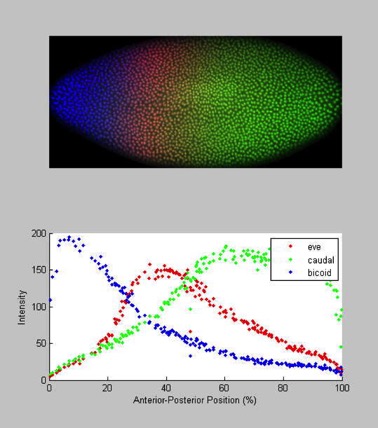

Figure 1When the egg is made, it is filled with mRNA provided from the mother (maternal mRNA). That mRNA is not evenly distributed throughout the egg. An important example can be seen from this A.P. question.

The first diagram below shows the levels of mRNA from two different genes (biocoid and caudal) at different position along the anterior-posterior axis of a Drosophila egg immediately before fertilization.

Figure 2

Figure 2The second diagram shows the levels of the two corresponding proteins translated from the mRNAs along the anterior-posterior axis shortly after fertilization.

Based on the diagrams, which of the following conclusions is best supported by the data?

- Bicoid protein inhibits translation of caudal mRNA.

- Bicoid protein stabilizes caudal mRNA.

- Translation of bicoid mRNA produces caudal protein.

- Caudal protein stimulated development of anterior structures.

Obviously, this is after many rounds of nuclear division. Based on the image, it appears to be before the cell membranes have formed. This is a syncytium, lots of nuclei in one huge cell. If you want to learn more about how these maternal effect genes set up the initial polarity, check out the images here.

Figure 3

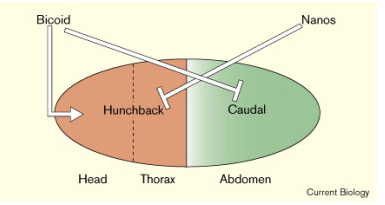

Figure 3And here is a representation of how two additional genes, Hunchback (yes, that’s its name) and Nanos interact. Just as Bicoid blocks Caudal, Nanos blocks Hunchback. Overall, you get a pattern of gene expression you can actually see as stripes on the embryo.

Figure 4

Figure 4Mid-Blastula Transition (MBT)

After formation of the blastula, or “ball of cells,” a critical change happens called the “mid-blastula transition.” At that point, cells have formed and transcription and translation of embryonic genes begins. These gene expression patterns are regulated by where in the anterior/posterior and dorsal/ventral axis the cell finds itself.

These embryonic genes then specify further what cells are going to do in the particular area.

Here is a link to another site that shows how some of these genes set up.

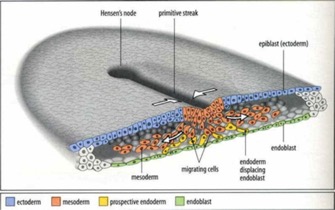

Gastrulation

The next big event is Gastrulation, which involves migration of the cells into three “germ” layers, known as the endoderm, ectoderm and mesoderm. This is stimulated by a morphogen made by specific cells. In humans, it’s called bone-morphogenetic-protein 4 (BMP-4), which is one of the Transforming-Growth-factor superfamily proteins (TGF was just the first one characterized, so the family of related proteins are named for it).

These three germ layers form the basis for all the bilaterian forms, from the simplest worms to us. The regulation of their formation is the same throughout the animal world. They will give rise to structures that correspond to location (ectoderm the more outer structure, endoderm the inner ones and mesoderm the middle ones).

Ectoderm gives rise to skin (in humans), of course, but also brain and other structures. Mesoderm gives rise to most of the muscles, as well as the cells that make blood. The muscles in humans include the “smooth muscle” that contracts in the gut, as well as the skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle. The endoderm gives rise to a lot of the abdominal organs, the epithelium of the gut and epithelial cells that do gas-exchange (alveolar cells) in the lung. That makes sense based on what Connor is learning about lung evolution.

Figure 5

Figure 5I lifted a picture from this website, which is a pretty good page. Thanks “scienceblogs.com.”

From this basic body plan, imagine superimposing additional rounds of positional information with similar themes. Morphogens in local area diffuse, interact with receptors and stimulate pathways that include new tissue-specific gene transcription and further development.

How would that look at the genetic and cell biological level?

Well, for one thing, you would see not a novel overall developmental plan (as in, for the human, we do a specific human development), but rather layers of developmental plans. These would require new genetic switches, of course. Gene duplications obviously have occurred, as we see by whole families of genes encoding similar proteins that perform analogous functions in each successive pathway.

As I said, I know only a fraction of what is known and all researchers combined don’t know it all. But, the basic scheme seems reasonable.

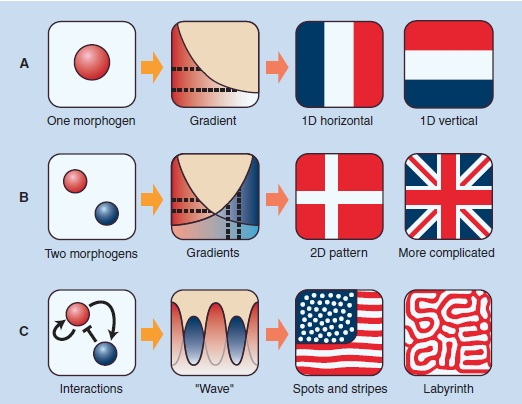

How do patterns develop?In the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, Alan Turing, the computer wiz who broke the Nazi Enigma code, started giving his attention to the problem of how you generate patterns in a developing organism. He came up with detailed mathematical models to explain patterns as overlapping gradients of “morphogens.” He had no idea what these were. We now know that they are gradients of proteins that are signal molecules that then regulate transcription factors, turning on developmental programs. I’ll write more on that later. His original models looked something like this:

Fig. 6

According to his models, a single morphogen diffusing from one spot could set up a gradient that could lead to a pattern of stripes along one axis. Compare the 1-D horizontal pattern above with Fig. 3 above. In reality, Caudal has an interactive relationship (see Fig. 4) with other transcription factors and sets up more complex patterns. How well his mathematical models have held up since the patterns he predicted started being detected in the 1960s and more dramatically in the 1980s.

I’ve often mused how much more we would have learned about morphogenesis early on if Alan Turing had stayed around. Sadly, he was convicted of the “crime” of being homosexual in 1952, was forced to submit to “chemical castration” and a year later killed himself (though some think his death may have been from accidental exposure to cyanide).

More Complex Patterns

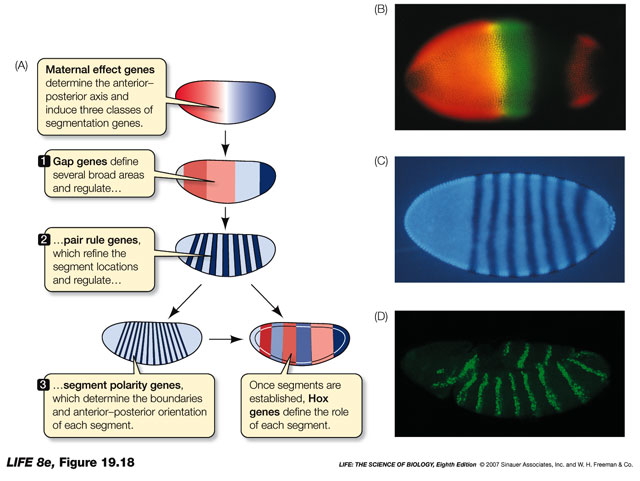

The following figure shows how maternal-effect patterns induce changes in early gene expression, which results in more complicated patterns in the early embryo.

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

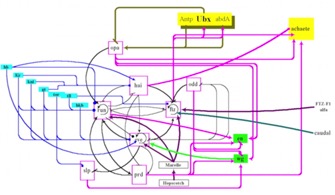

Some of the interactions are mapped out. However, I cannot tell you exactly how the whole thing works. These are a few of the genes and how they are thought to interact with each other’s function. I just include this to give you the idea.

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

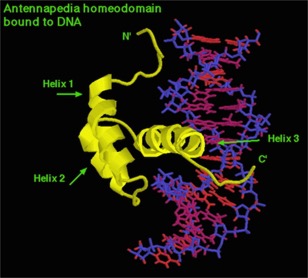

How do they work and why should you care?As mentioned above, most of these are transcription factors. There are also diffusing signal molecules (growth-factors and similar). They regulate entire developmental programs. In flies, the ones that regulate early embryogenesis control genes that identify what each segment is supposed to be. The latter ones were called “Homeotic genes.” They are the mutants that result in things like legs growing where antenna should be, or an extra set of wings.

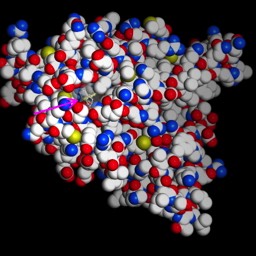

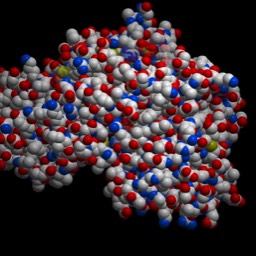

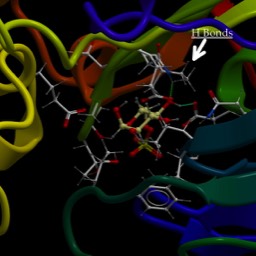

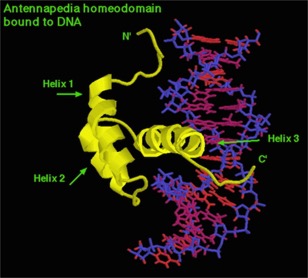

It turned out that they all had very similar sequences, encoding very similar proteins. In particular, one section of each gene was very similar. It became known as the “homeobox.” This encodes a short sequence of amino acids that forms three alpha helices separated by unstructured turns (called a “helix-turn-helix” structure). This is the DNA binding domain. The Homeoboxes of each gene differed in the sequence of amino acids that bound the specific sequence, but were otherwise similar.

Fig. 9

This is the antennapedia gene product bound to the DNA it turns “on.”

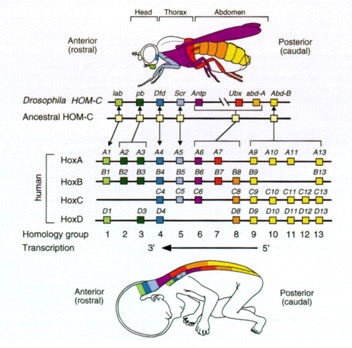

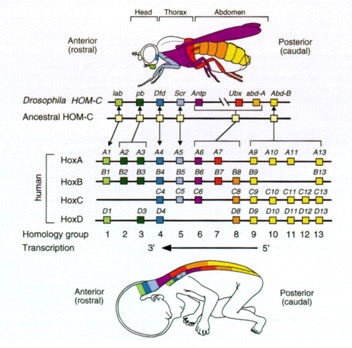

As for “why do you care?” It turns out that development in you works just about the same as development in flies. The Homeobox genes are found in you, where we call them HOX genes. The Hox genes come in a cluster of genes on one chromosome. There probably was one primordial HOX gene, perhaps controlling the anterior/posterior axis in a simple organism. Over time, this region of the chromosome has undergone many duplications, resulting in many copies of similar genes, each of which is responsible for particular steps in development. The more complex the organism, the more copies of the genes it has and the more developmental stages it goes through. Below is a color-coded alignment of the genes in flies and in humans. We show the same sort of section-specific expression of these regulatory genes. The identity of the genes is known and their arrangement on the chromosome is preserved from the original ancestral copy and is the same in flies and humans.

The pattern of expression from anterior to posterior is also conserved.

Figure 10

Figure 10

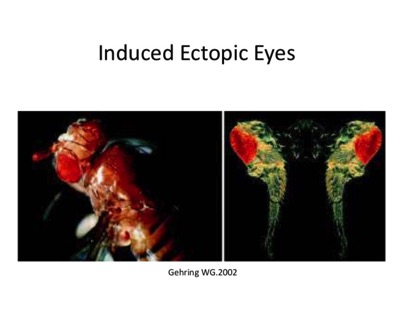

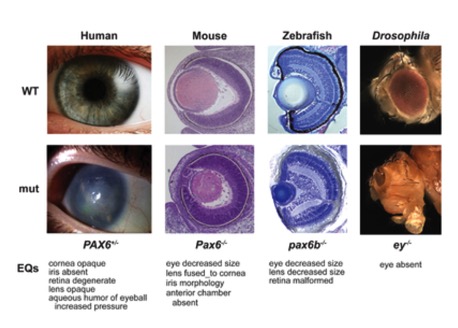

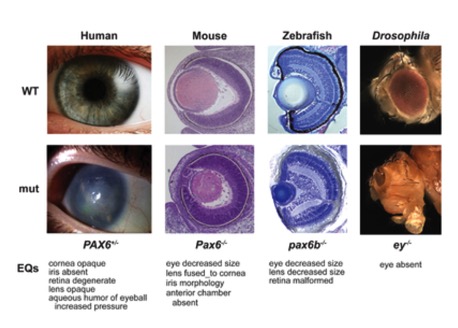

How similar is regulation of developmental genes in humans and flies? I've mentioned before a gene in flies known as "eyeless." It encodes a transcription factor, now known as Pax6, which is required to stimulate the development of the fly eye. Below is a figure showing how eye development is affected in various organisms with one or more mutant (non-functional) copy of Pax6

Fig11

Fig11

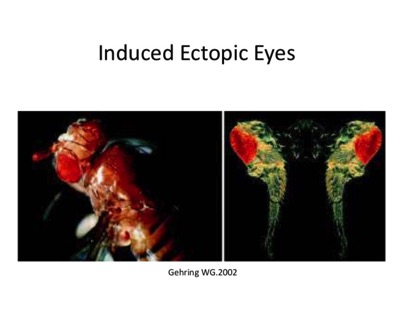

We know how to link genes up to specific promoters and put them into Flies. What would happen if you, for example, made the gene for Pax6 turn on in the leg of a fly? As you might expect, the fly develops eyes on its legs.

The figure below is even more striking, however, because the gene expressed in the leg of the fly is the human version of Pax6. That is, the human transcription factor turns on development of the fly eye. Cool, isn't it.

It turned out that they all had very similar sequences, encoding very similar proteins. In particular, one section of each gene was very similar. It became known as the “homeobox.” This encodes a short sequence of amino acids that forms three alpha helices separated by unstructured turns (called a “helix-turn-helix” structure). This is the DNA binding domain. The Homeoboxes of each gene differed in the sequence of amino acids that bound the specific sequence, but were otherwise similar.

Fig. 9

This is the antennapedia gene product bound to the DNA it turns “on.”

As for “why do you care?” It turns out that development in you works just about the same as development in flies. The Homeobox genes are found in you, where we call them HOX genes. The Hox genes come in a cluster of genes on one chromosome. There probably was one primordial HOX gene, perhaps controlling the anterior/posterior axis in a simple organism. Over time, this region of the chromosome has undergone many duplications, resulting in many copies of similar genes, each of which is responsible for particular steps in development. The more complex the organism, the more copies of the genes it has and the more developmental stages it goes through. Below is a color-coded alignment of the genes in flies and in humans. We show the same sort of section-specific expression of these regulatory genes. The identity of the genes is known and their arrangement on the chromosome is preserved from the original ancestral copy and is the same in flies and humans.

The pattern of expression from anterior to posterior is also conserved.

Figure 10

Figure 10How similar is regulation of developmental genes in humans and flies? I've mentioned before a gene in flies known as "eyeless." It encodes a transcription factor, now known as Pax6, which is required to stimulate the development of the fly eye. Below is a figure showing how eye development is affected in various organisms with one or more mutant (non-functional) copy of Pax6

Fig11

Fig11We know how to link genes up to specific promoters and put them into Flies. What would happen if you, for example, made the gene for Pax6 turn on in the leg of a fly? As you might expect, the fly develops eyes on its legs.

The figure below is even more striking, however, because the gene expressed in the leg of the fly is the human version of Pax6. That is, the human transcription factor turns on development of the fly eye. Cool, isn't it.